Why Haven’t the Television and Film Industries Learned From the Music Industry’s Mistakes?

A list of apps on an Amazon Fire TV.

As the writers strike ends, the actors remain on strike. Here we are, at the start of what should be a new season and it looks like we are close to possibly getting one. How did we end up here? It is painful to watch the television and film industries repeat the same mistakes that the music industry made two decades ago.

Back in 1999 and 2000, when the record industry lost its footing, it did so because there were many people who naively didn’t truly understand the value of music. Napster and sites like it were born out of frustration from some people who didn’t want to pay master-list prices for CDs, take them home and then end up “only liking one song.” While this approach may be the cause and the industry may have overplayed its hand with $18.99 list prices, it is still a myopic way to approach music. As a music collector around the same age as those who started this new digital “revolution,” I rarely found myself disappointed at that level by an album that I had purchased. If I only liked one song at first, I would listen to that album again until another song popped and blossomed. (Music sometimes takes time and patience to examine properly. It isn’t always the immediate sell.)

As a consumer and a lover of music, even at that time, I knew that even if I bought an album that I didn’t end up loving, I was still supporting the industry and the creators of art. The simple fact is, the kids downloading and sharing files on the sites for free saw what they got in return without perhaps realizing the lasting ramifications. Sure, if we all accept that the music industry was a money-grubbing, massive conglomerate, it all seems easy to justify, but in reality, what was really happening was the creators of the music that was being downloaded and traded for free were losing their livelihoods. If that happens over and over again, it creates a cycle that ultimately kills the industry.

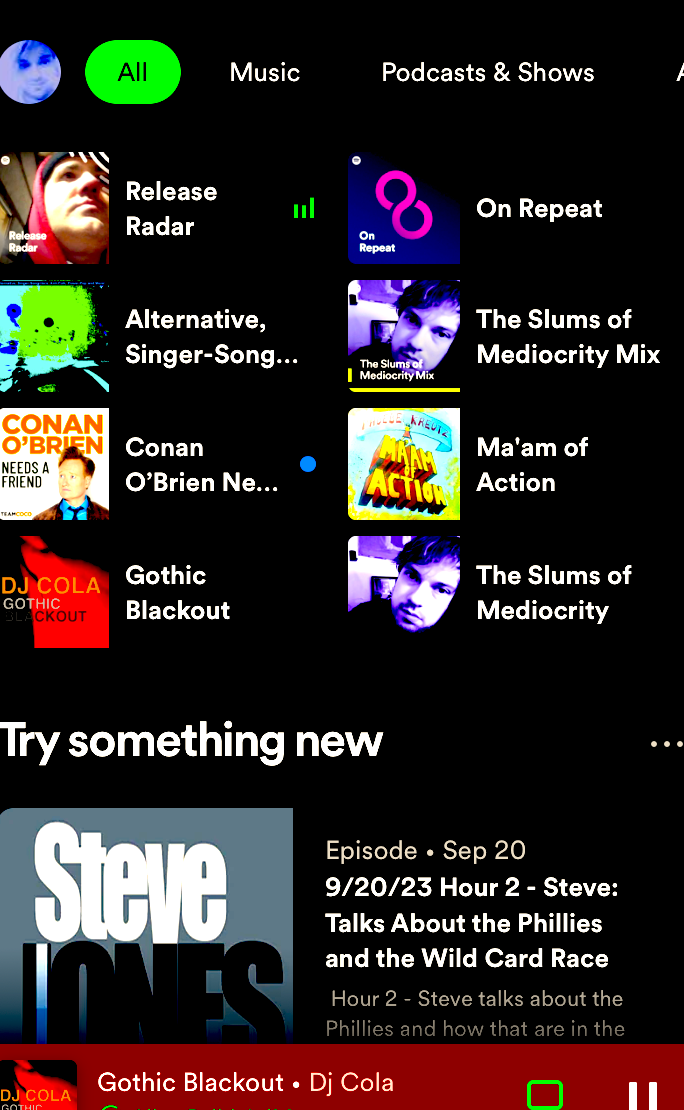

Spotify.

Riding high on massive sales at the start of the file-sharing boom, the music industry didn’t act quickly enough to counteract the catastrophic damage that was being done. Money was pouring in. Executives were getting rich off of album sales. Why should they worry? Nearly a quarter of a century later, artists making music are struggling. The major labels are now perhaps forced to go with what makes them easy money in the fastest way possible. Ultimately, this, in combination with the industry consolidation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which allowed companies to expand almost exponentially with fewer restrictions, resulted in a world where fewer musical innovations hit the mainstream. Sure, there will ALWAYS be excellent new music. (Don’t let anyone tell you that music isn’t as good as it used to be. That’s usually an embittered person, yelling at clouds, lacking the bandwidth to do the necessary research.) In today’s environment, however, it is more likely that the real musical innovators will be stuck in the fringes. Streaming royalties are low. (On Spotify,, it takes 1,000 streams to make roughly $4. On Amazon Music and Apple Music, the same streaming numbers could add up to roughly $5. Imagine you have a song with multiple writers and contributors, each dividing that pie! It isn’t sustainable.) Less mainstream experimentation happens now because the companies that operate the major labels have more to lose if risks don’t equal returns. The executives up on top are probably still getting bonuses, so ultimately the ones being increasingly fractured from the equation are the actual creators of the music, without whom, there wouldn’t be an industry.

In television and movies, it works the same way. The companies have merged to point of being too big to manage. The executives above are taking their huge payouts and not necessarily paying the writers, actors and the people behind the scenes what they are worth. “Cutting the cord” has in a way had the same effect as file-sharing did on the music industry. As we adjust to new digital means, we need to adequately and fittingly also adjust the pricing so that artists and creators can afford to create. It’s simple logic. If years ago, you spent $200 a month on cable but now you have four streaming services instead at $15 a month, each, that means that the industry now has to maintain the same level of entertainment with a net loss of $140 per month. Multiply that by millions of people and you see that it is an avalanche that threatens to destroy the industry.

The executives on top are still going to take more than their share and somehow justify doing so, so ultimately the people who actually create suffer from the consumers looking for a way to get more for less money. The greed and imbalance up top is a problem in nearly every American industry. (Look at what is currently happening with the auto-workers.) Somehow those in power still want us to believe the Reagan-era lie of “Trickle-Down Economics.” It sounds good on paper. In practice, it never works. It enriches those on top while resulting in inequality below. This approach has led to many huge entertainment companies facing major layoffs. Those below suffer while those above do their best to maintain their status.

Entertainment-wise, what does this mean? It probably means that in order to make this modern streaming system work in a way that is more equitable to the people behind the scenes, prices need to go up for both the music and the video streaming sites. A lot of people need to be able to afford to continue to make art. Of course, then that also creates a tricky balance.

When Max first appeared as “HBO Max,” the idea was that it was pretty much going to have virtually the entire HBO and Warner Brothers collections. Then Warner’s new parent company, Discovery came in and began removing titles. Like the old syndication model, more money is made by essentially leasing content out to other platforms. Perhaps we will see Disney begin to eventually do this with their content. The problem is, the completest aspect of these streaming services is a huge selling point. Lessening what is actually available on these apps diminishes their value. Plus, the compartmentalizing by production company made it easier to know and find certain programming on their respective apps.

Movies Anywhere is an app initially started by Disney. When you buy a digital movie from Amazon, Apple, Vudu, etc, and it is from Disney, Sony Pictures, Warner Brothers or Universal, this app allows you to link your services so that your movies show up in all of your collections. Paramount, Lionsgate and MGM have yet to join.

Ultimately, this is probably bad news. If you still have cable, as counteractive as it may seem, you probably shouldn’t cut the cord. If you listen to music on a music service, you definitely should still buy music whenever you can. Also, in addition to going to the movies, if you know of a movie or show that you want to be able to watch repeatedly, you should buy it, either in physical form or from a digital retailer to make sure you will have continuous access.

If you want entertainment to continue, its financial eco-system needs to be maintained. (It definitely needs to be severely retooled, as well, but we also don’t want it to cave in the meantime.) That being said, eventually ALL of the streaming services will have to increase their prices to make up the difference. Residuals are important because they support creators and afford them the ability to create even more.

In the end, those Napster kids probably thought they were sticking it to the labels. 23 years later, we have just traded overlords. We continue to barrel ahead into a more uncertain future.